The rings of Saturn are one of the jewels of the solar system, but their time seems to be short and their existence ephemeral.

New study They indicate that the rings are between 400 million and 100 million years old – a fraction of the age of the solar system. This means that we are lucky to live in an era when the giant planet has its own wonderful rings. Research also reveals that they could be gone in another 100 million years.

The rings were first observed in 1610 by the astronomer Galileo Galilei who, due to the limitations of the resolution of his telescope, initially described them as two smaller planets on each side of Saturn’s main body, appearing to be in physical contact with it.

In 1659, Dutch astronomer Christiaan Huygens published Systema Saturniumbecoming the first to describe them as a thin, flat ring system that does not touch the planet.

It also showed how their appearance changes, as viewed from Earth, as the two planets orbit the sun and why they seem to disappear at certain times. This is because their viewing geometry makes us see them on Earth periodically.

The rings are visible to anyone with a suitable pair of binoculars or a modest backyard telescope. Casting white against Saturn’s pale yellow orb, the rings are composed almost entirely of billions of water-ice particles, which fluoresce through scattering of sunlight.

Amidst this icy material are deposits of dark, dusty stuff. In space science, the term “dust” usually refers to small granules Of rocky, mineral, or carbon-rich material that is noticeably darker than ice. They are also collectively referred to as micrometeorites. These grains permeate the solar system.

Occasionally, you can see them enter Earth’s atmosphere at night as lightning bolts. The planets’ gravitational fields have the effect of enlarging or concentrating this planetary dust “fall”.

Over time, this fall adds mass to a planet and changes its chemical composition. Saturn is a gas giant with a diameter of about 60,000 km, about 9.5 times that of Earth, and a mass about 95 times that of Earth. This means that it has a very large “gravitational well” (the gravitational field surrounding an object in space) and is very effective at directing dusty grains toward Saturn.

collision course

The rings stretch from about 2,000 kilometers above Saturn’s cloud tops to about 80,000 kilometers, occupying a large amount of space. When falling dust passes through it, it can collide with ice particles in the rings. Over time, the dust gradually darkens the rings and increases their mass.

Cassini-Huygens was a robotic spacecraft launched in 1997. It reached Saturn in 2004 and entered orbit around the planet, where it will remain until the end of the mission in 2017. Cosmic Dust Analyzer (CDA).

Using data from the CDA, the authors in the new paper compared the current population of dust in space around Saturn with the estimated mass of dark dusty material in the rings. They found that the rings are no more than 400 million years old and may be as old as 100 million years. These may seem long time scales, but they are less than a tenth of the solar system’s 4.5 billion years.

This also means that the rings did not form at the same time as Saturn or the other planets. They are, in cosmic terms, a recent addition to the solar system. For more than 90% of Saturn’s existence, they weren’t around.

Death Star

This leads to another mystery: How did the rings form first, given that all the major planets and moons in the solar system formed much earlier? The total mass of the rings is about half that of one of Saturn’s smaller icy moons, many of which display massive impact features on their surfaces.

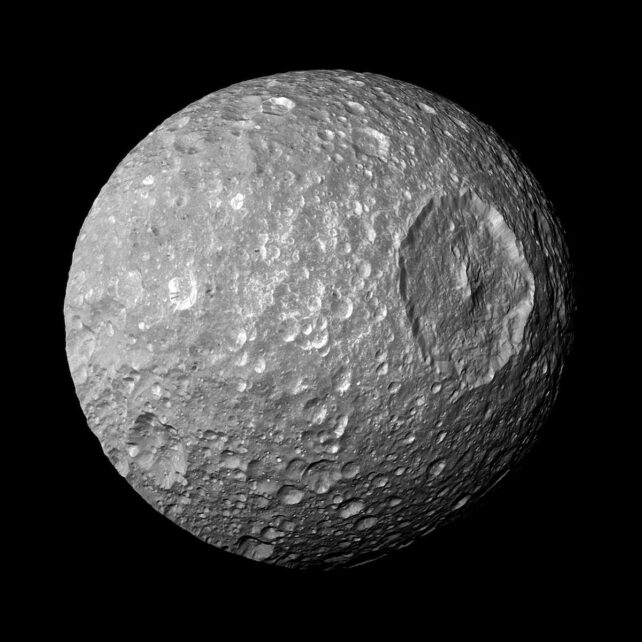

One in particular, Little Moon Mimasnicknamed the Death Star, on its surface there is a 130-kilometer-wide impact crater called Herschel.

This is by no means the largest crater in the solar system. However, Mimas is only about 400 kilometers wide, so this impact didn’t need much more energy to obliterate the moon. Mimas is composed of water ice, just like the rings, so it is possible that the rings could have formed from such a cataclysmic impact.

rain ring

Whatever their shape, the future of Saturn’s rings is in no doubt. The impact of the dust grains on the icy particles occurs at very high speeds, severing small fragments of ice and dust away from the parent particles.

Ultraviolet light from the sun causes these parts to become electrically charged across photoelectric effect. Like Earth, Saturn has a magnetic field, and once charged, these tiny icy bits are released from the ring system and trapped by the planet’s magnetic field.

Coordinating with the giant planet’s gravity, they are then directed down into Saturn’s atmosphere. This “ring rain” was first observed from afar by the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 spacecraft during their short flybys of Saturn in the early 1980s.

at recent days Paper from 2018 Scientists used dust counts, again from the CDA, when Cassini flew between the rings and the cloud tops of Saturn, to see how much ice and dust was lost from the rings over time. This study showed that about one Olympic-sized pool of rings is lost to Saturn’s atmosphere every half hour.

This flow rate has been used to estimate that, given their current mass, the rings are likely to disappear in less than 100 million years. These beautiful rings have a turbulent history, and unless they are renewed in some way, they will be devoured by Saturn.

Gareth DorianPostdoctoral Research Fellow in Space Sciences, University of Birmingham

This article has been republished from Conversation Under Creative Commons Licence. Read the The original article.

“Beer fan. Travel specialist. Amateur alcohol scholar. Bacon trailblazer. Music fanatic.”