Traditionally, pizza dough is made by allowing yeast to ferment flour and water until air bubbles form in the dough. But scientists in Naples are developing a new approach – one that doesn’t rely on yeast.

EMS-FORSTER-PRODUCTIONS / Getty Images

Hide caption

Caption switch

EMS-FORSTER-PRODUCTIONS / Getty Images

Traditionally, pizza dough is made by allowing yeast to ferment flour and water until air bubbles form in the dough. But scientists in Naples are developing a new approach – one that doesn’t rely on yeast.

EMS-FORSTER-PRODUCTIONS / Getty Images

Ernesto de Mayo has a severe allergy to the yeast in fermented foods. “I have to go somewhere and hide because I’ll be completely covered in bumps and bubbles all over the body,” he says. “It really is brutal.”

Di Mayo is a material world At the University of Naples Federico II where he studies the formation of bubbles in polymers such as polyurethane. He had to split the bread and pizza, which could make going out in Italy awkward. “It’s very difficult in Naples not to eat pizza,” he explains. “People were saying, ‘Don’t you like pizza? Why do you eat pasta? That’s weird.'”

When Paolo Iaccarino shows up to work on his Ph.D. in Di Maio’s lab, the graduate student quickly reveals that on the weekends, he’s a pizzeria—that is, a pizza maker at a legitimate pizzeria. He’s been making a lot of pizza over the past several years—”tens of thousands, sure,” he says.

So Di Maio put Iaccarino and another graduate student, Pietro Avallone, to work on a project to make pizza dough without yeast. The results of this scientific and culinary experiment were published in the Tuesday edition of fluid physics. Di Maio pulled up another colleague: chemical engineer Rossana Pasquino who studies the flow of materials, everything from toothpaste to ketchup to plastic. “Pizza [dough] It’s a funny substance, she “explains,” because it flows, but it also has to be like rubber. It must be flexible enough [when it’s cooked] To be perfect when you eat it.”

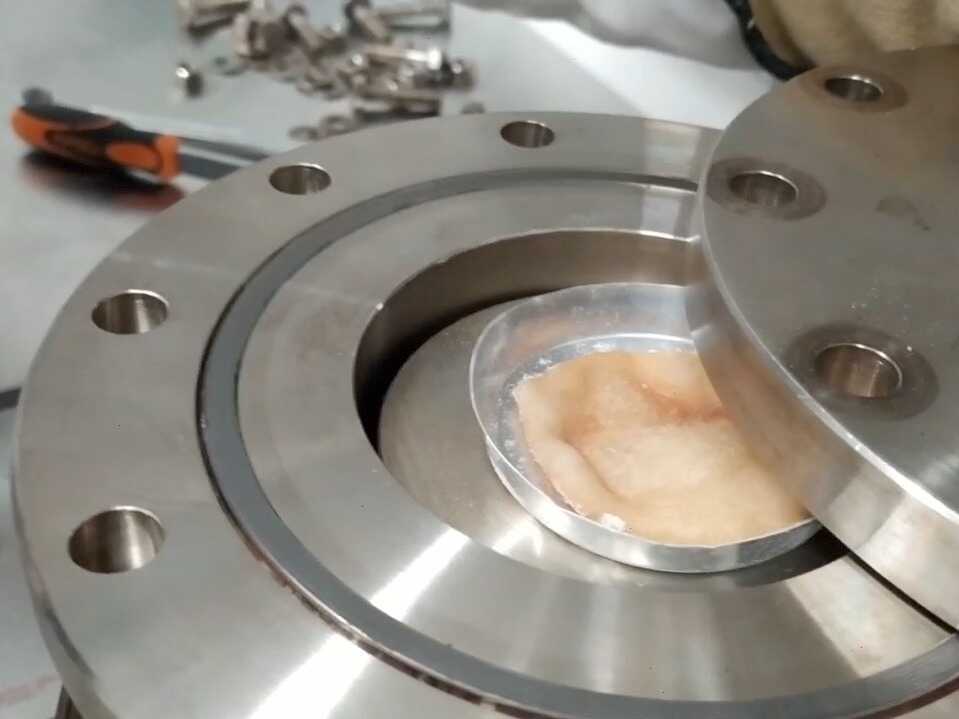

These tiny pizzas, just a few inches wide, were made in a lab in Naples using a new method for raising dough that doesn’t contain yeast.

Ernesto Di Maio

Hide caption

Caption switch

Ernesto Di Maio

These tiny pizzas, just a few inches wide, were made in a lab in Naples using a new method for raising dough that doesn’t contain yeast.

Ernesto Di Maio

It’s within this unique substance that yeast traditionally does its job. “Yeast are tiny microbes and they eat the sugars in the dough,” says David Ho, a physicist at the Georgia Institute of Technology not involved in the research. When they digest sugar, they “burp” [carbon dioxide], and create bubbles because the dough traps bubbles inside. “Let the dough rest or firm, and those cavities grow, and inflate them. Then, when you bake the pizza, air bubbles are cooked directly into the dough, creating that light, heavenly texture that is, a bubbly sponge,” Hu says.

However, the yeast is killed by the heat. Francisco Migoya, Head Chef at modern kitchen, a group of chefs, scientists and artists focused on culinary innovation. “There’s nothing alive in there anymore,” he says, especially for Neapolitan pizza, which he says is cooked at up to 800 degrees Fahrenheit.

The challenge for the Italian researchers, then, was to get the same height of pizza dough but without the yeast. Rossana Pasquino set out to measure the physical properties of regular dough in order to best replicate it in its unleavened version. She even had Iaccarino make pizza at his pizzeria using a temperature sensor baked into the dough.

The team’s breakthrough came when Di Maio thought of using compressed gas to form and inflate bubbles in dough, an approach that took years to perfect with polyurethane. They have tried both helium and carbon dioxide.

Notes

Time-lapse video of a yeast-free mini pizza dough rising due to gas pressure.

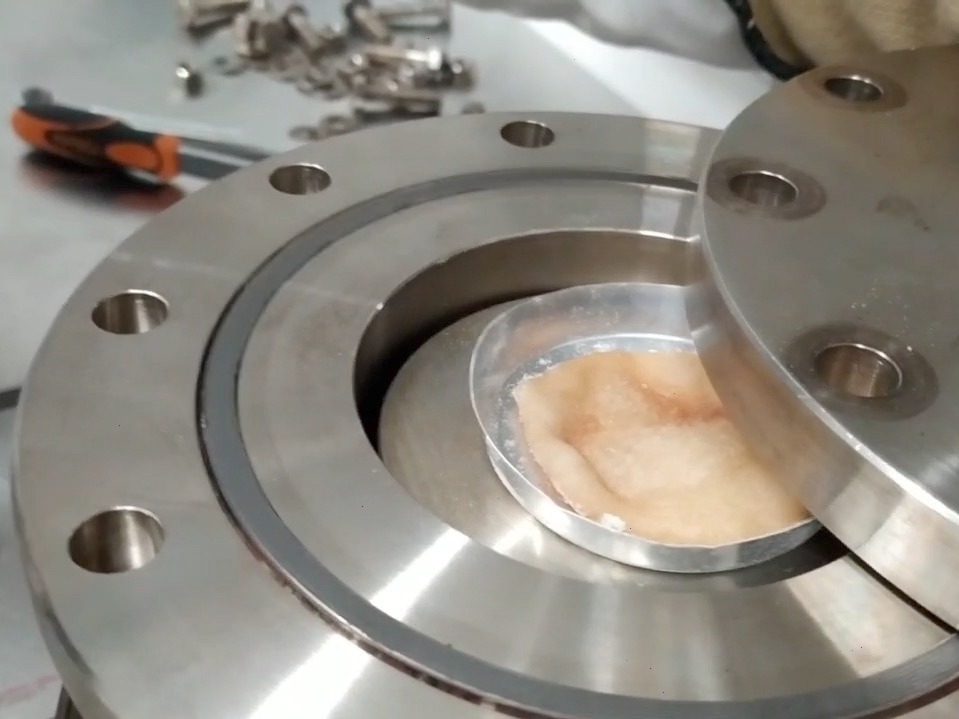

They then switched to autoclaves, a type of pressurized oven typically used for sterilization to kill dangerous bacteria, viruses, and fungal spores. In this case, the team put unleavened dough (made of only flour, water, and salt) into an autoclave and at the right time, temperature and pressure, they submerged it with gas. (This approach is somewhat similar to carbonate soda.) Then, as the scientists gradually released the pressure and increased the heat, the bubbles grew and the dough rose as it baked.

Test pizza dough is ready to be removed from the autoclave.

Ernesto Di Maio

Hide caption

Caption switch

Ernesto Di Maio

Test pizza dough is ready to be removed from the autoclave.

Ernesto Di Maio

Since their autoclave was small, the result was a handful of small pizzas, each half The size of a penny. The finished pizza dough had an airy texture and the taste was, according to Ernesto Di Maio, “just like yeast pizza.”

But not everyone is convinced. “Yeast does many things for dough, besides leavening, like the flavors you find, and complicating aromas,” says Migoya of Modernist Cuisine who was not involved in the experiment. “I’ll really need to taste this to make sure of it [they’re] Tell him what kind of objective truth.”

Paolo Iaccarino (left), a materials scientist, works as a pizza maker or pizzeria at a pizzeria on the side. He brought his experience with the dough to the lab to try out yeast-free pizza.

Paulo Iaccarino

Hide caption

Caption switch

Paulo Iaccarino

Migoya adds that yeast is ubiquitous in our environment. So even in the dough where no commercial yeast is added, there is still a bit of airborne yeast that will end up inside. (In fact, flour and water turn into a sourdough starter when that airborne yeast is encouraged to stay in the mixture.)

Migoya notes that baking powder or baking soda can also be used to create a rise without commercial yeast, in combination with an acid like yogurt or lemon juice, but it’s not a 1:1 substitute for yeast.

Rosana Pasquino likes that the approach she and her colleagues developed relies on a physical process, rather than a chemical additive like baking powder. She also appreciates that yeast-free pizza can save time because one won’t need to wait for the dough to rise or prove. Unfortunately, this approach isn’t quite ready for home bakers looking to improve their pizza dough with the latest science because most of us don’t have access to the specialized autoclave required to inflate the dough.

Pizza student and graduate Paolo Iaccarino admits that his dough is not for the average pizza lover. Instead, it’s an alternative for those with dietary restrictions. “If you think of generations of pizza-makers in Naples,” he says, “you certainly can’t say, ‘Well, take the pizza, put [it] In the trash, use pizza as a complete replacement. “

However, Pasquino says the researchers are already dreaming of expanding their method for use in a pizzeria. So the next step is for them to get a bigger autoclave to make a 10-inch pizza. Pasquino admits she probably won’t eat it. “I love pizza, actually. The problem is it makes me fat,” she chuckles. This may be the next challenge to overcome.

“Beer fan. Travel specialist. Amateur alcohol scholar. Bacon trailblazer. Music fanatic.”